There is a serious myth doing the rounds that the retirement of Australia’s ‘baby boomers’—ie, those born between 1946 and 1961—will trigger a massive new wave of housing supply that will swamp incoming demand and depress prices.

This fiction was exemplified in an article last week by the commercial property advocate, Chris Lang. Without resorting to statistical evidence, Lang likely terrified many retirees with his sensational claim that if they didn’t get rid of their homes within the next 12 months they would have to wait until 2025:

“Baby Boomers are facing an enormous challenge. And the sad fact is that they are probably not even aware of the problem. You see, if they haven’t sold their traditional inner-suburban homes before 2012 they need to be prepared to hold onto them until 2025, because there simply won’t be a market for that type of property before then.”

Based on the best available government forecasts, Lang’s statements are both factually flawed and misleading. Indeed, the opposite is very likely true: over the next 15 years there will be a much larger absolute increase in the number of non-retirees (aged under 65 years) in Australia relative to those aged 65 years and over.

The ABS and BIS Shrapnel project that we will have a net increase of 3.7 million new persons aged between 0 and 64 years compared with 2.0 million retirees. This will result in 2.3 million new ‘households’ added to Australia’s conurbations, who will need to buy or rent a home in which to live.

As I will show below, whether baby boomers decide to downsize or not will have no impact on this tsunami of population-growth driven housing demand.

A proper understanding of these issues requires one to dive into the data. And the starting point for any such analysis is, of course, population projections. Thankfully both the ABS and Treasury produce comprehensive estimates of Australia’s population change out to 2050.

One interesting characteristic of the ABS’s analysis is that they have consistently underestimated Australia’s population growth and have, as a consequence, been forced to repeatedly revise up their projections (see the first table below).

In 2003, the ABS projected that there would be 26.4 million people living in Australia by the end of 2050 (today there are 22.7 million residents).

In 2005, they upgraded this base-case projection to 28.2 million folks. And then in 2008 they revised it again to 34.2 million persons. That is, a 30 per cent increase over their 2003 numbers.

The Treasury then came along and threw a further spanner in the population works with its 2010 Intergenerational Report. Harnessing seemingly conservative assumptions, the Treasury concluded that we would, in fact, have 35.9 million residents living in Australia by 2050 (a stunning 36 per cent increase over the ABS’s 2003 estimates, as illustrated in the next chart below).

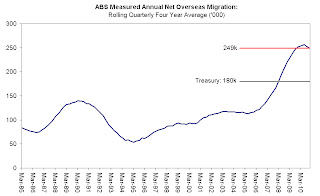

The bizarre thing about the Treasury analysis was that they presumed a very substantial slowdown in the pace of net overseas migration from our 249k per annum rate over recent years to just 180k per annum between 2012-2050. This is the reverse of what one would reasonably expect given Australia’s ageing population, which, Treasury forecasts, ultimately creates financial mayhem for the nation.

The Intergenerational Report tells us that there are currently five people of working age for every retiree. By 2050 Treasury thinks this will decline to 2.7 workers for every aged person. At the same time that an ageing population is driving up the government’s health and pension costs, the number of workers in the economy paying taxes will shrink. This results in what Treasury euphemistically calls a ‘fiscal gap’ from 2030 onwards: that is, government spending starts to exceed government revenues, which precipitates perpetual deficits and a sharp rise in government debt (see next two charts).

As Treasury notes, one partial solution to this problem is to import more skilled labour. Aside from being working members of the community, migrants tend to be younger than the existing residents. The ABS estimates that 85 per cent of migrants are under the age of 40, compared with 55 per cent for the resident population.

One objection to immigration is the allegation that Australia is an intrinsically xenophobic country. While this is refuted by cross-sectional studies of international attitudes to immigration (where Australia ranks as one of the more open-minded nations), it does not fit with the cultural facts either.

More than one in four (27 per cent) of all current Australians were born overseas. Nearly one in two of us (48 per cent) have at least one parent born in another land. We have, therefore, an exceptionally multi-cultural society. Much like the United States, we are an immigrant nation.

Notwithstanding our economic needs for more productive workers, Treasury assumes that our annual intake between 2012 and 2050 is about 25 per cent lower than recent averages (see next chart). I don’t think there is any good reason for this, and I strongly suspect that it was motivated to avoid punching out a 2050 population number that started with a “4”. In view of public concerns about infrastructure, amenities and congestion generally, a government forecast that our population is going to double within four decades would be politically tricky. Much better to simply allow the numbers to creep up on us, as they have done in the past.

So how many new households will Australia have over the next 15 years, and what does this mean for the number of new dwellings that will have to be built to accommodate them?

BIS Shrapnel recently addressed this question. In recognition of the repeated revisions to Australia’s population projections, and the latest immigration trends, BIS asked the ABS to combine their 2008 base-case scenario (known as ‘Series B’) with their higher-growth ‘Series A’ option (and some other assumptions), to create an up-to-date benchmark for Australia’s population change.

Based on this analysis, BIS conclude that Australia’s population will likely increase by 25 per cent to around 28.3 million people by 2026. That means there will be 5.7 million new Australians within 15 years. About 45 per cent of these folks arrive organically via (net) births, while 55 per cent will be immigrants.

BIS projects that this translates to about 2.3 million new ‘households’, with, on average, 2.5 persons per household, by 2026.

Now before I address the issue of the demand for homes relative to any available supply, it is instructive to parse this population data more thoroughly.

It turns out that Australia actually has three population bubbles emerging over the next 15 years: the current baby boom; the children of the ‘boomers’; and the boomers themselves.

As the chart below shows, there will be 2.6 million new ‘workers’ aged between 20 and 64 years added to the population by 2026 that will need to buy or rent homes. In contrast, the number of retirees will only increase by 2 million.

If we then look at the total rise in the non-retiree share of Australia’s population, the figure increases to 3.7 million persons (ie, between 0 and 64 years) that will require homes.

If we move from individuals to household units, BIS forecast that the number of working ‘households’ aged 20-64 years will increase by 1.2 million compared with a 1.1 million increase in non-working retiree households over the next 15 years.

A key take-away from this analysis is that the overall, 2.3 million increase in the number of Australian households has to be accommodated. Irrespective of whether they are renters or home owners, we will have to build dwellings to house them.

Taking historical data on demolitions and unoccupied dwellings (eg, holiday homes, etc), BIS conclude that around three million new homes will have to be added to the current dwelling stock over the next 15 years.

This is a herculean construction challenge. It would represent a 33 per cent annual increase in the number of new homes that have been built on average over the last 15 years. BIS does not think we will get there, and forecasts a smaller 28 per cent annual rise in housing supply, which results in a cumulative dwelling stock deficiency of about 240,000 homes by 2026 (see next chart).

Whether retirees choose to downsize or not will have no impact on the fact that we will be short circa three million homes. If some retirees choose to downsize, that will be good news: it means that the 1.2 million new ‘working’ households will have an opportunity to buy larger homes in established suburbs that are relatively close to their labour markets. But we will still need to build new homes for those retirees selling their properties. That is, the overall demand-supply equation is unchanged.

Based on the latest Productivity Commission report into aged care, the balance of risks seems to lean in favour of many retirees staying put. The ordinarily conservative PC have recommended that the Commonwealth fund a subsidised ‘equity release’ (or ‘reverse mortgage’) program that would enable retirees to cash-out the equity built up in their homes without selling them.

Under the PC’s proposal, the cost of this loan would accrue at just 2.5 per cent per annum (or the inflation rate) until it capitalised up to some maximum level. At this point, the government would stop charging interest (as happens with standard reverse mortgages), and the retiree would not have to repay the loan until they died or sold the property.

There would likely be huge demand for such a cheap and effective product. We estimate that if all retirees who own a home today took one of these products out, the government would liberate about $150 billion in funding to help aged-care. And since the government would have an asset on its balance-sheet—ie, the loans—there would not, in principle, be any increase in net government debt.

Assuming that many retirees want to remain in close proximity to the suburbs in which they have spent most of their lives, the end game is going to be higher city densities.

In 1921, only 42 per cent of Australians lived in metro areas. Today that figure is 64 per cent, which is projected by the ABS to rise further over the next decade and a half. Increasing densities in existing cities provides for powerful ‘network effects’ and scale economies, which is why this has been the dominant urbanisation trend in recent times.

Denser cities are also more environmentally friendly with a lower carbon footprint compared to dispersing households across the country, and having to transport them long distances to and from labour markets.

Contrary to some incorrect claims, Australia’s housing problem is going to be one of too much demand, not excess supply.

Real-time, stream-of-consciousness insights on financial markets, economics, policy, housing, politics, and anything else that captures my interest. Tweet @cjoye

The author has been described by News Ltd as an "iconoclast", "Svengali", a pollie's "economist muse", and "pungently accurate". Fairfax says he is a "Renaissance man" and "one of Australia’s most respected analysts." Stephen Koukoulas concludes that he is "85% right", and "would make a great Opposition leader." Terry McCrann claims the author thinks "‘nuance’ is a trendy village in the south of France", but can be "scintillating" when he thinks "clearly". The ACTU reckons he’s "an enigma wrapped in a Bloomberg terminal, wrapped in some apparently well-honed abs."