In one corner we have journalists at The Economist newspaper, who in their latest survey make the extraordinary claim that Australian house prices are overvalued by 56 per cent using their preferred benchmark. In the other corner we have a crowd of the most respected economic minds in Australia, including the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Commonwealth Treasury, almost all market economists, and leading house price index providers, such as RP Data and Rismark.

This latter cohort essentially contend that The Economist does not know what it is talking about. They argue that Australian house prices are not materially overvalued, and there is no reason to believe that they must suffer precipitous price falls in order to obtain some more desirable valuation benchmark. This group have also produced vast reams of analysis showing that robust demand- and supply-side fundamentals underpin Australian housing valuations while dwelling price-to-income ratios remain unexceptional by international standards. In fact, recent research by Rismark has demonstrated that house price growth in both Australia’s capital cities and our regional areas has not kept pace with disposable household income growth since the end of the last cycle in 2003.

It was only last week in The Economist’s backyard, the City of London, that the RBA Governor, Glenn Stevens, was tossed a question about whether he was worried about Australian housing valuations. In the past--most notably in 2002 and 2003--the central bank has not hesitated to express reservations. Yet Stevens responded:

“Well, let’s establish a few facts…for the past year or two, house prices haven’t done anything much at all…we continue to see arrears rates on mortgages very low by global standards ...We don’t have a gearing up going on now …So I’m not terribly troubled by – I don’t think we have huge rises going on... that’s probably not top of my list of worries…The other thing I’ll say is that it’s quite often quoted very high ratios of price to income for Australia, but if you get the broadest measures, a country-wide price and a country-wide measure of income, the ratio it about 4 ½ and it hasn’t moved much either way for 10 years. And that is higher than it used to be, but it’s actually not exceptional by a global standard as far as I can see.”

While the typically conservative RBA thinks Australia’s housing market is sitting pretty, The Economist’s survey suggests it is massively overvalued. In order to decipher who is right or wrong here, one has to dive into the detail.

The Economist arrives at its 56 per cent estimate by taking the ratio of median house prices to median rents, and then comparing current levels with their “long-run average”. There are many technical problems with this approach. One obvious issue is that we do not observe rents for more than two-thirds of the entire housing stock, which is ‘owner-occupied’. So The Economist is actually comparing the yields on rental properties with the prices of owner-occupied homes. Imputed owner-occupied rents are likely to be different to those deriving from investment properties given the far greater control rights associated with the former.

But this is a trivial error in the scheme of things. There is a much deeper problem with The Economist’s logic, which both the RBA and we here at Rismark have repeatedly highlighted. Let us explain.

Anyone can compare the current observed values of a range of economic indicators, such as interest rates or inflation, with their ‘long-term’ averages. But we need to ask ourselves whether this is an informative exercise, or potentially misleading.

For example, applying The Economist’s way of thinking to Australian interest rates would lead one to conclude that current rates are much too low. Indeed, The Economist's analysis implies that Australian Government bonds are massively overvalued since today's 10 year yields of 5.5 per cent are more than a third lower than the 30 year average of 9 per cent.

Yet the body that sets interest rates--the RBA--has repeatedly told us of late that present day lending rates are, in fact, “a little higher” than their long-term averages. So what is going on?

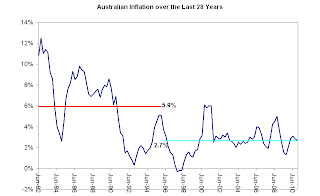

As an alternative, let’s examine inflation. Today the RBA believes that the acceptable rate of consumer price inflation is around 2.5 per cent per annum. Yet the 30 average rate is 4.2 per cent per annum. Does this mean that the RBA should substantially revise up its inflation target? Of course not.

These variables were not selected by chance. The truth is that the crux of this debate hinges on how inflation, interest rates, household debt, and house prices have varied over the last three decades.

In its survey, The Economist takes median house prices and median rents over the last circa 30 years—which is the longest horizon over which these data are publicly available—and calculates a long-term ‘average’ ratio, which it assumes to be the ‘correct’ benchmark. It then compares current house prices and rents to this 30 year benchmark. If current ratios are above (below) this 30 year average, then The Economist claims that they are over- (under-) valued.

The Economist does not question whether the old housing ratios might be nonsensical to today’s home owners as a result of: (a) fundamental changes in the structure of the economy wrought by the fact that interest rates over the past 15 years have, on average, been 43 per cent lower than interest rates in the 15 years that preceded that period (see first chart below); (b) the fact that average inflation since the middle of the 1990s has been 55 per cent lower than inflation in the 15 years prior (see second chart); or (c) the fact that the rise of two-income households and the female participation rate in concert with a near halving in the nominal cost of debt might have triggered a once-off upward increase in household purchasing power, and hence housing valuations.

Now we have tried to replicate The Economist’s analysis using the longest publicly available time-series of median houses prices and median rents in Australia, which one can purchase from the Real Estate Institute of Australia. This covers the period June 1982 through to December 2010.

If we adopt The Economist’s method, we conclude that the current ratio of median Australian house prices to median rents is about 38.7 per cent above its 28 year average. We do not know how The Economist gets its 56 per cent estimate, but ours is in the same general ball park.

Interestingly, we can get a 56 per cent number if we look at inflation over this exact same period. Australia’s current inflation rate of 2.7 per cent would have to rise by 56 per cent to agree with its long-term average of 4.2 per cent since June 1982. But, of course, nobody in their right mind would claim that this makes any sense. It is just that The Economist uses this logic when they analyse housing.

One can undertake a similar exercise with interest rates. The headline mortgage rate today is 7.8 per cent. The average headline rate since June 1982 is 9.9 per cent. Does this then mean that Australian mortgage rates are currently way too low? Applying The Economist’s method, Aussie home loan rates should rise by 27 per cent in order to correspond with this historical benchmark.

As we mentioned earlier, imposing The Economist's logic on the Australian government bond market would imply that it is in the throes of an enormous bubble since yields are more than a third lower than their 30 year average.

To really understand what is going on here one needs to examine the time path of three economic variables: inflation; interest rates; and rental yields. (Note that a rental yield is simply the inverse of The Economist’s price-to-rent ratio (ie, a rent-to-price ratio).)

As you can see from the chart above, Australian inflation has steadily declined from its high and volatile double digit levels in the 1980s to sit within the RBA's 2-3 per cent per annum target band during most of the past two decades. This has allowed the central bank to in turn reduce interest rates.

In the RBA’s view, the long-term reduction in inflation has mainly been a function of the early 1990s recession and its adoption of what is known as an ‘inflation target’. The RBA’s 2-3 per cent target was first taken up in about 1993, and more formally enshrined in an agreement between the RBA and the Treasurer in 1996.

Between 1982 and 1995, mortgage rates in Australia averaged 12.8 per cent. Since the start of 1996, they have averaged 7.3 per cent (or 43 per cent less). The RBA considers today’s mortgage rate of 7.8 per cent to be slightly “above” its historical average because the RBA believes that the history that is relevant to today starts with the application of the inflation targeting approach to monetary policy in the early 1990s. Yet we don’t hear The Economist claiming that Australian mortgage rates are too low. (In fact, Australian mortgage rates are today amongst the highest in the developed world.)

The RBA has regularly argued that the structural decline in inflation, and the resultant downward shift in nominal interest rates, in turn drove a once-off upward shift in household’s borrowing (and purchasing) power. This has been reflected in the once-off jump in household debt levels, which basically occurred between 1996 and 2003. This marked rise in household borrowing power also boosted their purchasing power and hence the value of readily leveraged assets, such as houses.

In the following chart, we track the change in Australian mortgage rates and rental yields since 1982. The message is clear: the secular decline in nominal interest rates has propagated a corresponding fall in yields.

Our final chart tells the same story by comparing Australia’s dwelling price-to-disposable household income ratio (bottom line) with Australia’s rent-to-dwelling price ratio (top line) over the last two decades. Observe how these ratios look like mirror images of each other. The common driver has been inflation and interest rates.

The RBA believes that as interest rates started to stabilise at their new, much lower levels in the late 1990s, and households got comfortable with the idea that both rates and inflation were unlikely to jump back to the double digit levels of the 1980s, there was a consequential upward increase in the valuation 'level' of housing assets. This had been fully priced by the early 2000s, which is why the two ratios track sideways thereafter.

To be clear, the RBA's ability to get inflation under control (and thus cut the long-term level of nominal interest rates) caused increases in the household debt-to-income, household debt-to-GDP, house price-to-income, and house price-to-rent ratios. In the jargon, these were 'level effects' rather than 'growth effects'. This means that the very rapid double digit credit growth of the 1990s and early 2000s will not be repeated anytime soon.

Unless you believe that we are going to get double digit inflation and 17 per cent mortgage rates, which most observers think are near impossibilities, the housing market benchmarks of the 1980s are irrelevant to home owners in the second decade of the 2000s. The same principle applies to The Economist’s analysis.

It would, of course, be wonderful if our ever-changing, multi-dimensional world could be judged by crude long-term ratios that blissfully ignore all sorts of key facts. Unfortunately, that's just a recipe for confusing further an issue that already has many confused.

Looking ahead, it is highly likely that Australian house prices will track household earnings in what PIMCO's Bill Gross has aptly described as the 'New Normal'.

Real-time, stream-of-consciousness insights on financial markets, economics, policy, housing, politics, and anything else that captures my interest. Tweet @cjoye

The author has been described by News Ltd as an "iconoclast", "Svengali", a pollie's "economist muse", and "pungently accurate". Fairfax says he is a "Renaissance man" and "one of Australia’s most respected analysts." Stephen Koukoulas concludes that he is "85% right", and "would make a great Opposition leader." Terry McCrann claims the author thinks "‘nuance’ is a trendy village in the south of France", but can be "scintillating" when he thinks "clearly". The ACTU reckons he’s "an enigma wrapped in a Bloomberg terminal, wrapped in some apparently well-honed abs."